Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) released a report this week to coincide with the 1st anniversary of the Ebola outbreak. One year on from the first confirmed case in Guinea I wanted to give a brief update on the situation in Sierra Leone, and to outline the next steps for the quick and comprehensive eradication of the Ebola virus.

Let’s be clear: Sierra Leone is still in a situation of severe Ebola crisis. The MSF reports that “there is no room for mistakes or complacency; the number of new cases weekly is still higher than in any previous outbreak.”[1] The number of new Ebola cases has declined from its peak level but the number has spiked recently in Guinea and, as we are about to investigate, has stabilised but only slightly reduced since mid-January in Sierra Leone. The NERC and government agencies have been working hard with international assistance to contain the virus, but what we have learnt from previous outbreaks is that we are now entering the most difficult stages of eradicating the disease.

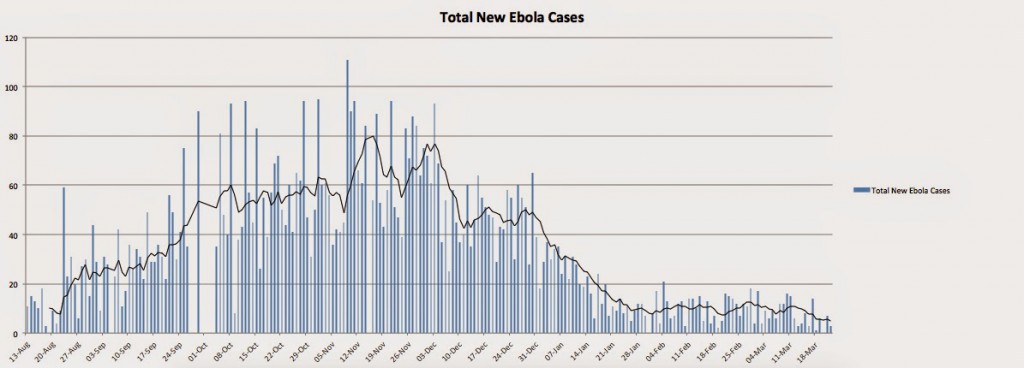

During the months leading up to December 2014 we saw a large spike in the number of Ebola cases nationwide.

During mid-December the number of new cases dropped to around 45 per day. In the period immediately after Christmas we saw these numbers swiftly falling to the 22nd January, at which point there was a relatively stable 12 new cases per day.

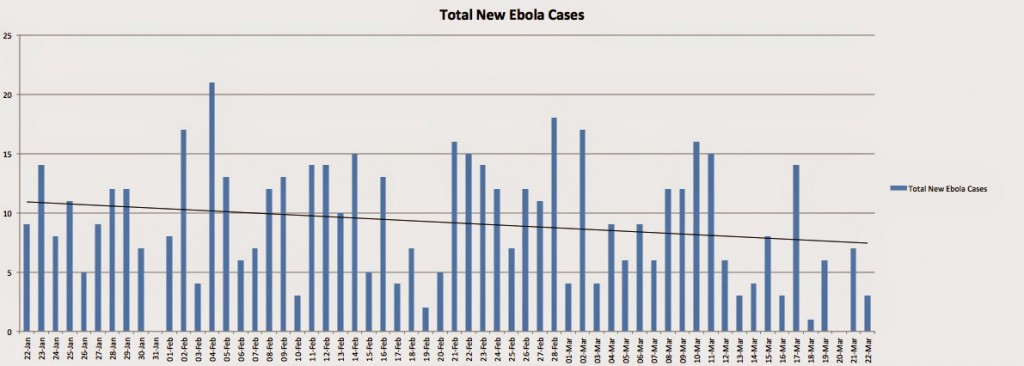

The graph below shows the daily new cases since the 22nd January

This period of general stability is accompanied by a slight decline in new Ebola cases, from 12 per day to 8 on average. This is a positive movement and one that would suggest the work being done by government agencies, NGOs and charities is helping to stem the spread of Ebola.

There are several reasons for the downward turn in the number of new cases, including: establishment of protocol and accepted standards of containment; provision of treatment and testing facilities; acquisition of ambulances and frontline care supplies; and the effectiveness of the information campaign. The country’s national infrastructure and the international aid community learnt many difficult lessons in the incredibly trying months leading up to Christmas, and it will need to take those lessons in to the near future in order to eradicate this disease.

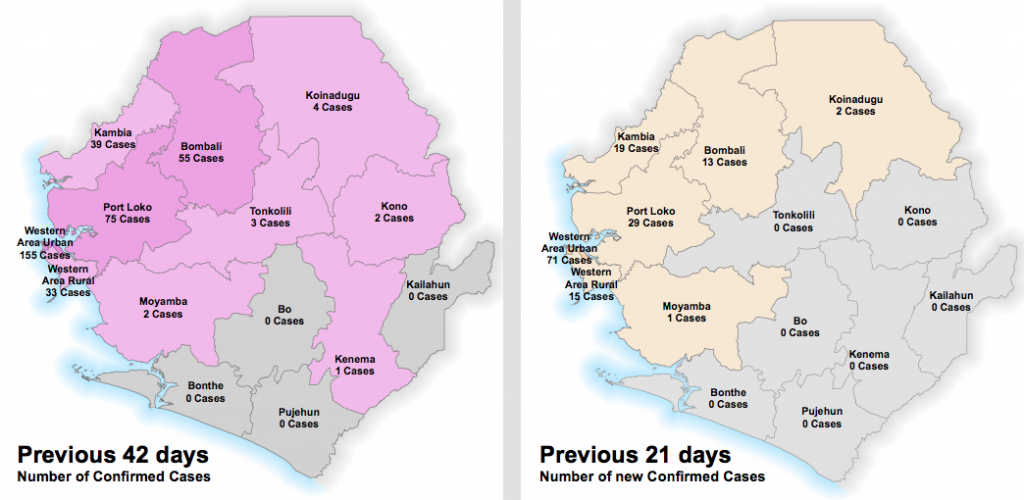

Whilst clearly indicating a general downwards trend, the graphs do not give us the full picture. What we are actually seeing in Sierra Leone is an increased focus of the virus in certain areas. The Western Urban Area, which includes the capital, Freetown, is the single hardest hit region in the country; over the whole outbreak it has suffered 26% of all cases. Port Loko is the second most heavily hit region with 17% of all national cases. Despite the total number of new cases falling, both the Western Urban Area and Port Loko have seen a disproportionate increase in the share of new cases since 23rd January: the Western Urban area accounts for 37% of new cases during the period as opposed to 25% before 22nd January; and Port Loko accounts for 23% up from 16% in the previous period.

One of the main influences of this increased focus is the high population density in these regions. Ebola, and contagious viruses in general, are much more persistent in urban environments with close living quarters and low levels of sanitation. Both of these regions in Sierra Leone have many people, often living in squalid conditions: the perfect environment for the virus to spread.

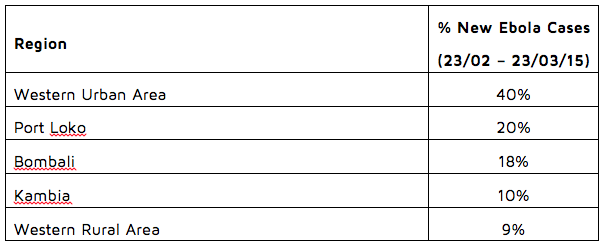

The past month, from 23rd February to 23rd March 2015, has shown further polarisation of newly reported cases: 8 regions show 0% of new cases whilst 1 region shows 1%. The remainder is broken down as follows (please note that the discrepancy between stated numbers and 100% is as a result of rounding):

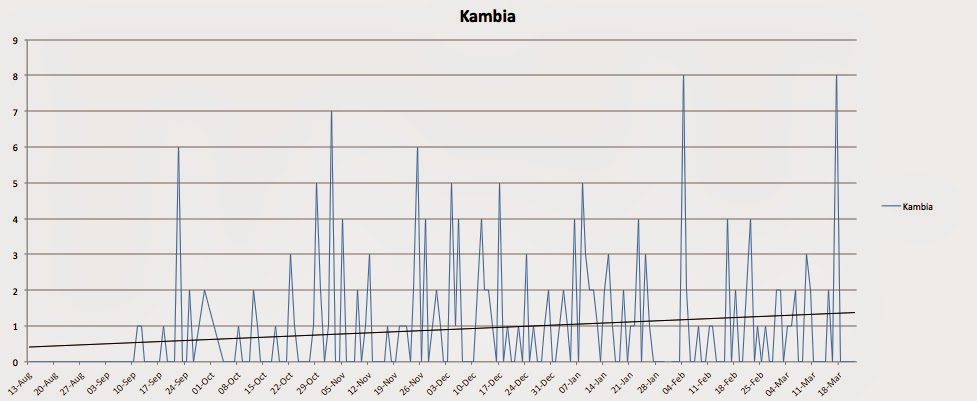

Kambia is one of the situations that bares scrutiny, and one that demonstrates one of the potential risks in the path to recovery for the country. Kambia is located on the road between Freetown and Conakry, the capital Guinea, and has an estimated population of 40,000 people.[2] Lying on the transit road between two Ebola-suffering country capitals has fostered a breeding ground for Ebola in recent months.

The question begs: how do we stop Ebola? The accepted method is one that has been practiced throughout the outbreak: contact tracing. This simple but laborious process is to, one-by-one, identify all of those individuals that confirmed sufferers of Ebola may have come in to contact with. Hans Rosling, a consultant health statistician working in Liberia illustrates this process very succinctly with a current example in the video below. Please skip forward to 10:13 for the explanation of a localised outbreak and for the method and survival expectations of contact tracing

The challenge of declaring Western African countries free from Ebola is still a large task. It is easy for the government, health officials, NGOs, and the international community to become complacent when thinking about Ebola. The case of Kambia highlights just how important it is to retain focus on the situation in hand, and to re-allocate resources as is necessary.

Contact tracing is a laborious process, but these Ebola-stricken countries are much better equipped now to deal with the current levels of the outbreak. Contact tracing teams are experienced in how to effectively find the necessary information without imposing too greatly on the suffering victims or grieving families, and they will lead the country’s efforts to eradicating the virus. Simultaneously, the Ebola treatment centres are steadily improving their survival rates and have significantly increased capacity for sufferers of the virus.

Today, Sierra Leone has once again gone in to a 3 day lockdown. If ever there was a need to remind ourselves that Ebola is still having a serious affect on Sierra Leonean life, then this is it. People throughout the country will be unable to leave their homes throughout the weekend except for to pray. Please spare a thought for our staff and students in this difficult time, and for those Sierra Leoneans whose lives have been so disrupted and, in some cases, torn apart by death and grief. It is clear that we have much work to do. The continued effort by the government, international aid organisations, NGOs, and smaller charities like EducAid, will help to speed up the process of eradication. As many of you will be aware, we operate schools in both of the highest risk regions in the country, and so are very necessarily worried for the wellbeing of our students and staff.

We continue to need all of the support that we can gain in order to combat the effects of this virus. We hope that, once our schools are open again, we will be able to once again return to what we do best, and begin to educate and prepare the next generation of independent Sierra Leoneans.

We know that this will be a tough ask, so if you can spare anything to help towards our goal it will be much appreciated. If you would like to do so, you can donate here.

EducAid, fighting for a life #AfterEbola

[1] http://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/msf1yearebolareport_en_230315.pdf

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kambia,_Sierra_Leone