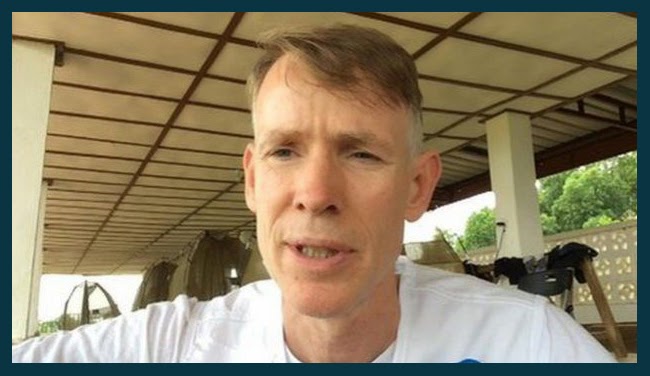

Inside Ebola Junction: Dr. John Wright

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

After half an hour in my protective suit, I feel as though I’m in an out-of-control sauna. My goggles are fogging up, and my vision is starting to get impaired. After an hour I have a pounding headache, and sweat is literally pouring down my body filling my boots which squelch when I walk. I start putting up an IV line, but I’m thick-fingered with my double gloves. I can’t see very well out of my steamed-up windows, so I do the right thing and pass it over. However, this is just mid-morning, and I dread to think what the ward rounds are like in the middle of the African Heat. Eventually I stagger to the doffing area. The doffing monitors are the Kings of the Ebola centres; they have no qualifications, little literacy, but in the doffing station they have all the power. With their chlorine sprayers on their back, they are the ones who will de-contaminate me and get me safely through to the other side.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Ebola really is a terrible disease: pain; fever; exhaustion; confusion; diarrhoea and vomiting; and bleeding. Safi, the older woman, has against expectations improved from her near-moribund state yesterday. Isatu, the younger woman, who was well on admission deteriorated yesterday, but after ramping up treatment she’s showing some signs of improvement. On this morning’s ward rounds she was really distressed: she says that she is not worried about her own life – about dying from Ebola – but she is worried about her children. Her 5-month old daughter died last month, but her other children are now abandoned at home with no one to support them. Meanwhile, Ibrahim, the one we were least worried about, has deteriorated rapidly. He is confused and almost catatonic, a zombie-like state of late-Ebola. During the first 36 hours since our Ebola Treatment Centre opened, these 3 patients were jostling for position on the critical list, but today it is Ibrahim that looks most likely to die.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

There is a maxim for Ebola hospitals, and that is to expect the unexpected. This afternoon we were taken by complete surprise when two ambulances turned up in quick succession. It is the second that causes the greatest problem. On the adult-sized stretcher lies a tiny 2-year old girl, silent with fear. There are now 7 of us in full personal protective equipment. I pick her up in my arms; I know there is a risk that she may pull at my goggles, but she is so small, so fragile, so afraid , that I cannot resist.

She clings to me with the reflex of a toddler, and the stoicism of an African child. She is beautiful. I asked the ambulance nurse about the child. We have no name, no parents, no record, no history. The nurse had been at the primary healthcare clinic when the child

The story is that her mother has Ebola. The story is that her mother is here in our hospital.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

On the afternoon ward round, I find Ibrahim unresponsive. It is difficult to feel a pulse with the double-gloving, and it is difficult to check his pupils with my fogged up goggles, but it doesn’t take long to conclude that he is dead: our first Ebola fatality. I stretch out his arms and his legs, and I cover him in a blanket. The chlorine sprayer is twitchy as she washes y hands, and she drops her sprayer. She knows that Ebola is most dangerous at death, and she is scared of the body. And after the close contact that I have had, she is fearful of me. A sudden sadness descends on the team. Ibrahim was young and fit, and almost symptomless on admission. Ebola is an unpredictable grim reaper.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

It’s my last morning in Moyamba, and I have just heard great news back from the laboratory: our first negative Ebola test from one of our patients. It’s Safi, a woman in her 60s who was very close to death when we admitted her. This means that we have our first survivor just one week after opening. The first of many I hope. How do you cure Ebola? One patient at a time. I couldn’t have wished for a better souvenir

‘Moyamba’ is Mende for ‘send for us’, which they did. We turned up far too late to the starting line for this life and death race, but we have arrived in time to make a contribution. Our Ebola hospital will isolate and care for the last patients on the bumpy tail of this epidemic, and our work with the community will help stop spread. The real heroes of this struggle are not the international community, but the health workers in the communities of Sierra Leone who have fought and died on the front-line of this terrible war. I leave full of admiration for their bravery; Sierra Leone: Lions on the Mountain”

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

The radio piece was originally broadcast on Radio 4 on 24th February of this year, and is available here.

Thanks to the Dr. John Wright and the BBC for providing such a compelling listen.

Following this is a short aerial video of the Moyamba Ebola Treatment Centre where Dr. John Wright worked – it really shows the scale of the operation going on there.